When I flung myself into graduate school for my Ph.D. I was certain that I was going to study baboons, gorillas, chimpanzees – the big flashy primates. These were the primates that everyone was studying and I was certain that if I wanted to make it as a biological anthropologist, I had to stick with these primates.

I wanted to be learn everything, from functional morphology to human evolution and everything there was to know about craniofacial growth & development. I dutifully explored the skeletal system in these primates, their social behavior and diets, their evolutionary history and loved it! Then I decided to take a class on fossil primates with a professor that terrified me because of how much he knew about teeth and bones, but I jumped in with both feet and quickly realized I would be lucky to just keep my head above water. This professor opened the world of strepsirrhines (lorises, bushbabies, and lemurs) up for me and I was never the same.

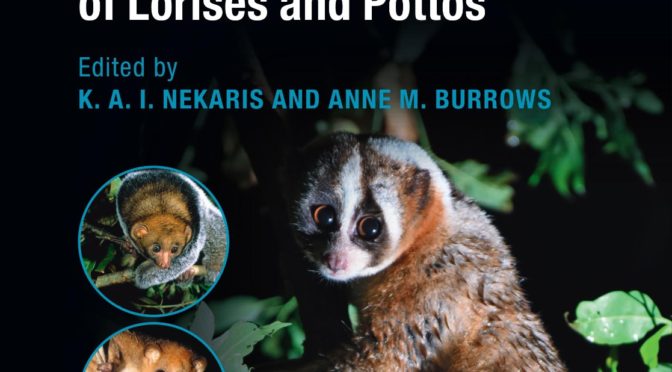

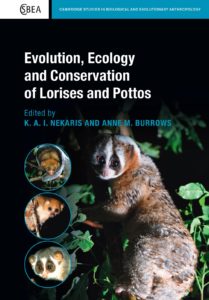

Lorises and pottos took over most of my research questions and I’m still going! Here were these mysterious primates that rarely, if ever, came down from the trees, came out mostly in the dark, and had unusual skeletal systems and teeth like I had never seen before. They were social but in a very different way than baboons and apes. I was drawn in by all of these factors but I was especially keen about what these gorgeous and unusual primates could tell us about primate origins and evolution. Lorises and pottos display some of the characteristics that we think the earliest primates may have also had, such as relatively small body size, nocturnal and arboreal lifestyle, and small social groups. Given all of this, I figured that the more I knew about lorises and pottos, the closer I could come to understanding how the first primates developed, what factors were important in their evolution, what their social behavior might have been like, what they ate, and the general story of primate evolution. So I put my time and focus into the world of lorises and pottos. While I was blown away by the highly specialized hand and foot morphology and their dental specializations, I started asking questions about how they were related to one another, whether our conceptualization of their relationships was correct, and how such geographically distant species could be related to one another at all.

If we can understand how lorises and pottos are related, what the major pressures were in their evolutionary history, and how both their morphology and behavior were shaped then we can have a better shot at understanding how primates charged forth onto the landscape some 50 million plus years ago and what environmental variables were important in the process. In the end, this knowledge may very well help us with preserving primate species, especially the lorises and pottos.

Anne M Burrows, Duquesne University