It is now 11 years since we launched Slow and Slender Loris Outreach Week. When we thought about this week back in 2011, the idea was to create a unity among loris projects around the world.

We were asked by a number of zoos especially to make it a whole week to allow a further level of outreach and also to accommodate aspects like school holidays. We are happy to say that loris researchers in every range country have now participated in SLOW either via holding events at their field sites, rescue centres or zoos; producing vital education materials about lorises and their conservation; via participating in international and online conferences; via publishing guest blogs; and sharing information to the world via the power of social media.

We are honoured to be featured as the main loris outreach event by National Geographic, Mongabay and Peppermint Narwhal, and to have been joined by artists from all over the world who use the week to showcase lorises in their creative media. Over the years some “competing” days have arisen, which can of course confuse the public and make animal days meaningless. As the first and oldest loris awareness event, covering all loris species as well as giving shout outs to the amazing pottos and angwantibos, we hope that loris projects will continue to celebrate SLOW and that we can continue with another decade of inspiring passion for loris conservation and bring a united and focussed attention to save a group of species that already receives too little attention.

This year’s theme: translocation

This year our focus was on “translocation”, which is becoming an increasing threat to lorises both slow and slender. Slow lorises have long been heavily traded to the extent that many conservationists think they are common in the wild. This is not evidenced by almost every wild survey, where for every site a loris is found, in dozens they are not. Where they are found, their densities are very low, largely due to their small family groups in large home ranges with extreme territoriality.

For species where good surveys exist, they are found more on forest edges and even in human habitats where shrubs and trees are dense and preferred foods happen to be grown or are pioneers. This means they are easily seen and easily caught, and also, being on the edge, it is easy for hunters to take them on their way out of the forest; at times when crops are failing, and hunters need extra money; when felling trees for almost any purpose including firewood (lorises cling to trees where they can be plucked away whilst most species run away). This means also that ALL lorises in an area can be caught and numbers in markets increase the perception that they are common. This combined with an age of first birth at 3 or 4 years; one offspring per year with a risky survival rate during dispersal; and risky dispersal through extremely human-dominated areas add to the risks.

In fact, the reason we started our decade-long field study of Javan slow lorises was because so many were dying in rescue centres due to lack of total knowledge about their care or that they were refused by rescue centres all together.

In addition, many rescue centres will not even take in a slow loris. The quotes I have heard over the last 25 years range from the idea that “money should be spent on the important species,” “a cage won’t be wasted on slow lorises,” “we saved it because it was easy to just put it back in the wild,” “we don’t need to know anything about their wild behaviour because it won’t make a difference – we already know about orangutans and they still die,” “we tried to fund raise for slow lorises but the public only cares about orangutans so there is no money to spend on them,” to more than one world renowned conservationist noting in almost the same exact words “nobody gives a f&*^ about slow lorises.” These disdainful attitudes were followed by an almost 100% death rate in monitored translocations. Our own work and that of East Asian Species Trust is finally finding some clues to how they can survive, but they clearly are still a very difficult species to put back into the wild. I reiterate a number of those reasons here.

Should we be translocating slow lorises?

Because of the lack of wild studies, many translocations should never take place at all! The IUCN suggests we should know the diet and behaviour of a species across multiple annual cycles in multiple sites before we even consider reintroducing them. Without proper knowledge of their wild behaviour, we are at risk of introducing animals into habitats with no food, shelter they would choose, and causing risk to resident populations. Indeed, starving to death, freezing to death or just becoming exhausted “looking for home” are all reasons translocated lorises have died.

Nationwide surveys need to be done to ensure that translocations are not just because surplus populations exist. We should be reinforcing populations or repopulating areas that have been hunted out. Instead, many rescue centres instead release slow lorises into the only known healthy populations. With their venomous territorial bites, diseases from markets etc that can be transferred to wild populations, this is a recipe for disaster. Furthermore, in many cases, lorises have been translocated into habitats where they never lived, into city parks, and into countries where that species never occurred!

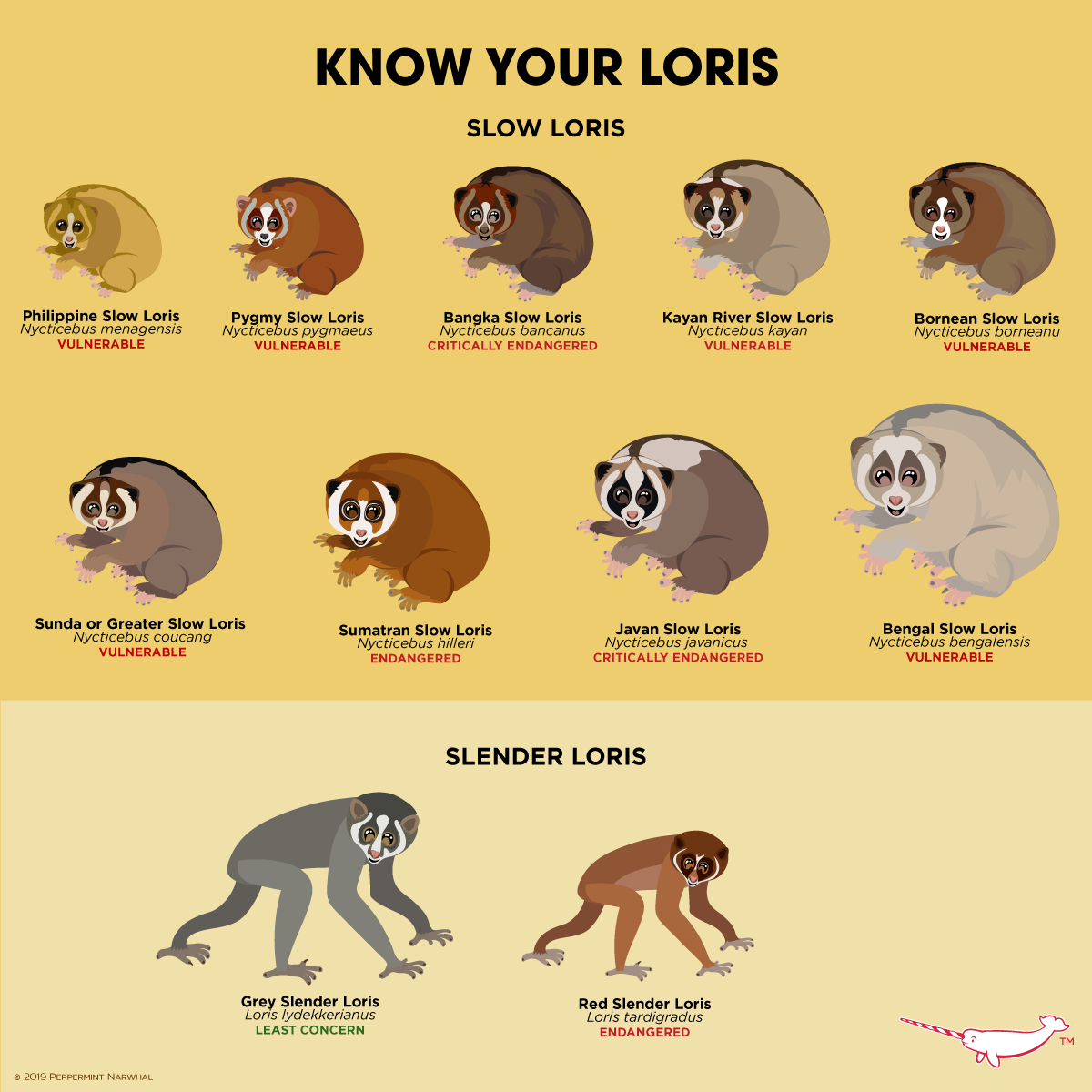

This is the case just for known species; introducing a species into a novel country can causing invasive species issues with ecologically similar animals. At the same time, slow loris taxonomy is far from being resolved. Many rescue centre workers do accept that there are newly recognised species that are actually on the IUCN Red List. And that there are likely further species to be uncovered, particularly if we apply the same taxonomic principles that are applied to other primates. Most people would be appalled if Sumatran orangutans were translocated to Borneo – or to the South of Sumatra. It boggles the mind to understand why this is okay for small species ranging from reptiles to rodents to birds – and of course slow lorises!

These and other issues were covered in my online seminar which can still be viewed on the Oxford Brookes University Primate Conservation Monday evening seminar series on Facebook. We are also soon to publish a paper on this topic with data collected regarding the increasing trend for potentially harmful translocations in collaboration with slow loris researchers Dr Nabajit Das from India, Dr Qingyong Ni from China, Sabit Hassan, Hassan al Razi & Marjan Maria from Bangladesh and our own LFP team from Indonesia. Information on good practice to help these issues from becoming exacerbated is available on the downloads section of our website. Happy #SLOW2022!